By Nicolas Rapold in the November-December 2015 Issue

Sabotage

Guy Maddin goes to war in Bring Me the Head of Tim Horton

Even by the debased standards of gallery installations and lobby art, Bring Me the Head of Tim Horton was displayed under subpar conditions at this year’s Toronto International Film Festival. Looping on a flat-screen affixed to one of the Lightbox theater’s lobby support columns, this collaboration between Guy Maddin and Evan and Galen Johnson competed for attention (during my morning visit) with the imminent arrival of Johnny Depp for the Black Mass press conference next door. As photographers jostled on the line to get in and ticket buyers milled about, the left-field making-of about the Afghanistan war film Hyena Road was barely even audible from the tiny bench that sat between the screen and an opposing wall a few feet away.

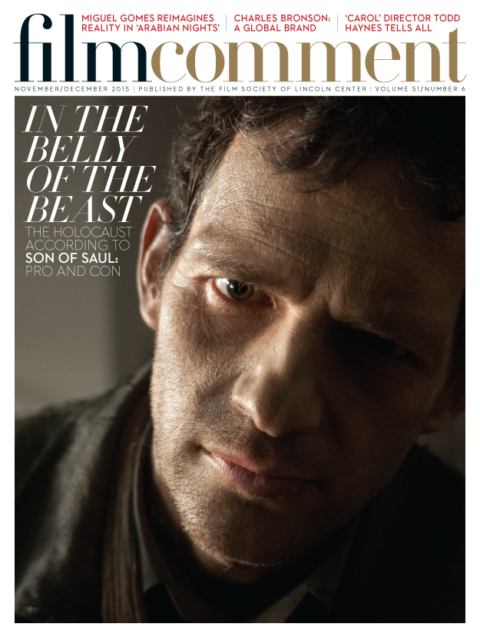

From the November-December 2015 Issue

Also in this issue

Perhaps Maddin could appreciate the peripheral presentation—he certainly sounded amused in an interview we did a few days later—because his film also exists alongside a piece of ersatz-Hollywood bombast. Directed by Canada’s actor/director/graying-hunk Paul Gross, Hyena Road tracks snipers and officers wrangling with villagers and Taliban forces in what the trailer describes as “54,000 square kilometers of insurgencies, tribal rivalries, and blood feuds.” Bring Me the Head of Tim Horton is Maddin’s wholly authorized film about the film that brings his spirit of absurd pastiche and voluminous hyperbole to bear on this drama “from the director of Passchendaele,” who is also apparently a friend.

Maddin introduces his 31-minute gonzo meta effort with an image of his prone figure lying somewhere in the Jordan badlands where Hyena Road was shot. He explains that he’s playing a Taliban casualty, and gripes comically about his fist-waving ambitions in a hard-boiled voiceover perhaps intended to mimic Gross’s tough-guy delivery. He vows to shoot a “Trojan Horse inside the Trojan Horse” as a “retort to [the] digestible adventurism” that is Hyena Road. What we get instead is a mélange of coverage of actors playing soldiers in desert fatigues, during takes or just rehearsing (or doing deep knee bends); computer voiceovers issuing sub-Debord pronouncements; re-colorized versions of scenes, including one supplemented by lasers and an Eighties straight-to-video synth score; and bouncy disco tunes recorded by Canadian hockey legend Guy Lafleur.

Bring Me the Head of Tim Horton

The closest these flagrantly uninformative digressions come to a standard featurette is a couple of outtakes of a producer doing a walk-and-talk TV-ad bumper. While earning Maddin some needed cash, this supposed promotional project burlesques the look of a seamless studio-grade war movie—and its very notion. It’s like any number of subversive reappropriations of mainstream genre cinema, except with the added nose-thumbing of having been done with full permission, during the production. But if Maddin expresses some frustration or resentment about Gross’s comparatively big-budget illusionism, he also can’t help but see the playful, bizarre, and beautiful possibilities in these expensive toys.

Originally intended to be a series of “pre-creations” of scenes from the film, using a different cast, Maddin and his co-directors ended up mostly filming alongside the official shoot. One precursor is Pere Portabella’s 1971 film Cuadecuc, Vampire, a parallax view of Jess Franco’s Count Dracula, but the seat-of-the-pants artistry is of a piece with Maddin’s The Forbidden Room, which was mostly shot “live” in Paris’s Pompidou Center. While Maddin’s personality combines self-effacing Canadianness and soul-baring excess, there’s a discernible edge to his aversion to patriotism. He’s mocking the macho spectacle of Hyena Road but can’t revel in its narrative pleasures in quite the same way as with the picture shows of yesteryear.

Does that make Bring Me the Head of Tim Horton, shown in TIFF’s Wavelengths section, Maddin’s first political film? The title alone is a provocation, taking the name of another hockey star in vain while somehow avoiding the wrath of the coffee chain he founded (which has franchise branches on Canadian military bases, including those in Afghanistan). However pungent you find the satire—and it is, unlike most such meta efforts, hilarious—the film feels personal and handmade in a way that’s fresh and intriguing even coming from this director’s perennially fertile imagination.