By Gavin Smith in the July-August 1999 Issue

All the Choices: Albert Brooks interview

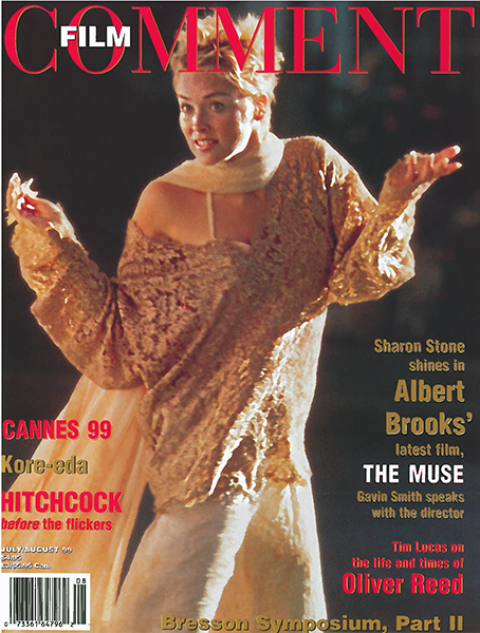

In Albert Brooks's new comedy The Muse, a Hollywood screenwriter (played by Brooks) attempts to reignite his stalled career by employing the services of a muse (Sharon Stone, demonstrating she's an impressive comedienne). Descended from one of the seven Muses of Greek myth, she boasts an impressive track record of divinely inspired careers—at one point she and Brooks bump into Rob Reiner, who exclaims, "Thank you for The American President." Expensive, demanding, and capricious, the muse rapidly takes over the screenwriter's life, requiring lavish treatment and eventually moving in with Brooks and his wife (Andie MacDowell).

From the July-August 1999 Issue

Also in this issue

Cowritten by Brooks and Monica Johnson, this satire of Hollywood is embellished with sharp, frequently hilarious observation of its ritual humiliations and shallow social and professional interactions, with notable contributions from Jeff Bridges as a self-absorbed Oscar-winning screenwriter friend, Steven Wright as Stan Spielberg (“I’m Steven’s cousin”), and Martin Scorsese in a self-parodying cameo. But at its core is the spectacle of a rational, down-to-earth individual who, faced with a career crisis that threatens the life of comfortable domestic affluence he has built for himself, succumbs with surprisingly few misgivings to an absurd New Age fix and gets more than he bargained for.

At Heart The Muse is less a broadside against the Industry than another of Brooks’s subtly offbeat cautionary comedies of modern anxiety. Once again, a Me Generation Everyman occupies an ideal lifestyle or system, blissfully unaware of its underlying precariousness. Whether it be the smug, callow filmmaker’s perfect experiment in documentary in Real Life (79), the impossible fantasy of “true love” in Modern Romance (81), the way a life of complacent materialism is exchanged for an equally deluded freedom of the road in the anti-Reagan-zeitgeist Lost in America (85), or ended altogether by the ultimate bummer of sudden death at the start of Defending Your Life (91), the Brooks protagonist is oblivious until too late. In The Muse, as in Mother (96) and Lost in America, the great central comic conceit is his adoption of an improbable radical solution: When your marriage fails, move back in with your mother to figure out why your relationships with women don’t work; when you don’t get the promotion you feel you deserve, quit, drop out of society, and go on the road to find yourself; if your writing career goes south, hire a muse and do whatever she instructs, even if you can’t shake the feeling you’re being shortchanged.

The striking consistency of Brooks’s comic vision is reinforced by the characteristic strategies he deploys. Almost every film is essentially a two-character piece in which Brooks pairs himself with an actress in an unstable or artificial, often domestic, situation; The Muse diverges from this scenario, if only through triangulation—this time Brooks gives himself two female leads to contend with—but still avoids the obvious. Instead of finding himself torn between two women, Brooks typically must endure the humiliation of being sidelined as his muse-for-hire bonds with his wife and inspires her to launch a line of home-baked cookies that win instant acclaim.

Brooks’s protagonists tend to be successful, yet average, creative types who write or work in advertising or filmmaking (one of the incidental joys of Modern Romance is its dead-accurate depiction of a film editor’s working life). His characterizations effectively refract the contradictions, compromises, and neuroses of the Baby Boom generation with its overdeveloped sense of entitlement and unapologetic materialism: narcissistic and controlling yet insecure and resigned, reflexively self-analytical yet lacking emotional self-honesty. It’s hard to think of another American filmmaker who has dedicated him/herself so completely to scrutinizing the foibles of his generational peers without becoming moralistic or sentimental.

This pattern of structuring comedy around a distinct personality-type is also evident in Brooks’s early work. His early-Seventies comedy bits for TV, two unique records, Comedy Minus One (73) and A Star Is Bought (76), and his six short films for “Saturday Night Live” in 1975-76 all emanate from a specific comic persona: smugly self-confident, oblivious to its own absurdity. This holds true from the early comic routines that established him, presenting supremely assured yet inept performers (a loquacious French mime, a ventriloquist whose mouth moves) through to his first feature, Real Life, the zenith of this mode. In formal terms an extension of Brooks’s “SNL” shorts, this mock-documentary parody of PBS’s landmark “An American Family” pushes the arrogance and narcissism of its main character to the point of implosion. Brooks’s next film, Kubrick favorite Modern Romance, a truly terrifying comedy of obsessive jealousy and loss of control, signaled a decisive aesthetic shift toward a narrative approach based in more dimensional character and psychology. Brooks’s subsequent films (and even a number of his performances for other directors, notably in James L. Brooks’s Broadcast News and I’ll Do Anything) are defined by the more complex experience of humbling misfortune and an ensuing struggle to overcome pervasive anxiety and regain existential terra firma.

While a cult of personality has deservedly formed around his compact oeuvre, the reductive perception of Brooks as merely preoccupied with neurosis erases any distance between Brooks and the characters he plays, and has more than once cued the glib tag of “a West Coast Woody Allen.” But his work has none of the latter’s self-regarding pretension, misanthropic cynicism, and self-pity. Moreover, it displays a formal integrity that has entirely eluded the ever-derivative Allen. Brooks’s distinctive filmmaking style is remarkably discreet and unemphatic; he has a light, deft touch, with a classical precision and economy, shooting and cutting his scenes in smooth, seamless successions of medium shots, with clean, high-key lighting. (“A style so distanced and disciplined it can only be termed analytical,” wrote J. Hoberman.) He also knows how to take his time: if you look at Mother you see scenes that last as long as ten minutes, and you’re never impatient to move on.

But perhaps because of his relatively sparse directorial output—six films in 20 years—even some of Brooks’s critical champions have called him an underachiever. I know what they mean. Brooks seems constitutionally incapable of going over the top, and he’s not interested in blowing the audience away. In his elusive sui generis brand of anti-sentimental, observational comedy, the comic possibilities of character and situation are always restrained by a defining sense of plausible reality and authentic, self-revealing emotional experience. This places him completely at odds with American comedy’s currently prevailing aesthetic—a parodic, cartoonish absurdism, fed on high energy, outrageous excess, and mock sentimentality—whose prime exponents include Jim Carrey, the Farrelly brothers, Ben Stiller, and the post-“Saturday Night Live” Adam Sandler and Mike Myers.

That he stands outside this mainstream is ironic indeed, since the rise of Brooks and peers like Steve Martin and Andy Kaufman in the early Seventies signaled the emergence of an oppositional sensibility that began to gradually displace the dominant postwar comedy establishment. “Jokes are disappearing,” said Brooks, the son of a member of the old school of standup, and in their place he installed a more conceptual kind of humor. It was apt that he was referred to as a “comedian’s comedian,” because he practiced a unique, at the time innovative brand of self-reflexive metacomedy that dismantled the familiar, seemingly moribund comedy formats—ventriloquism, impression, standup itself. And just as his first short film Albert Brooks’ Famous School for Comedians (72) and the subsequent “SNL” shorts pressed ahead in the same vein, targeting TV and documentary, one of the not-so-incidental pleasures of Brooks’s films is their sustained, sardonic commentary on the ubiquity of movies and their illusions in his characters’ lives. Lost in America, a film that opens with Rex Reed being interviewed by Larry King about what’s wrong with today’s movies, epitomizes this, with its yuppie couple’s recurrent recourse to Easy Rider as a blueprint for the rest of their lives, and its casting of director Garry Marshall (who is superb) as an amused, all-business Vegas casino manager. In The Muse, the Los Angeles-born-and-bred Brooks returns to the ground zero of movie-made America, resuming his interrogation of the emotional life and values of his generation as it navigates treacherous waters.

Are you sticking your neck out with this film, a story about someone who faces rejection in Hollywood?

I guess since that’s what I’ve always done, it doesn’t feel so much like sticking my neck out. I’ve never come from a safe place; I sort of began my whole comedy career sticking my neck out. So I don’t know any better. Hopefully, I’m always going to be honest enough with what I do where I can leave my neck out. I just don’t consciously think in terms of safe and unsafe.

You don’t feel there’s a pattern in your work of exploring specific fears?

I think I do. I think that’s the nature of writing. I don’t think it would be fun to do it otherwise. Unless you do that, it doesn’t get exciting. I’ve never made a sequel; I’ve never gone to a place that was familiar to me. I had seen lots of different movies about this town, and those scenes, to me, don’t ring true. The people I’ve seen in other movies, cast as studio people or agents, they’re just not what I believe is really there. I wanted a chance to put my two cents in. Casting Mark Feuerstein as opposed to Martin Short as the studio executive makes a big difference. I try not to do these parts in a clichéd way; I at least try to make them real enough that you don’t even have to know about the business to know it’s real.

Why is your work more rooted in realism than most current comedy?

Well, I didn’t think about it like, I’ll do this and they’ll do that. I once had an agent say to me, years ago … we were having some discussion over an argument about a studio project and he said, “Gee, I don’t know why you always take the hard road,” and I said, “You think I see two roads?” You don’t really analyze what you do—you just do what you’re able to do, and if you stick around long enough, then maybe you’ll start your own category or you’ll fit into a category.

When I started, one of the first things I ever did was “The Dean Martin Summer Show.” The producer, after seeing one spot, gave me eight shows, and said to me, “Do you have material?” I said, “Yes,” and I really didn’t, and he said, “Okay, you’ll start in four weeks.” And I went home and figured out what kind of a comedian I would be, and I came back and I showed him my stuff, and he said to me, “You know what? If you do this kind of material you’re going to have trouble your whole life, because you’re ten feet above the audience.” I said, “I don’t know what you’re talking about—this is all I know how to do,” and he took this long pause and he said, “Okay, that was all I wanted to hear. Go do it.” You just do what you know. Some people are right in the mainstream from the get-go. They don’t ever have a problem with that, that’s just who they are.

What inspired the film?

The idea of something or somebody that is going to sit on your shoulder and guide you through this stuff. It’s so romantic and, obviously, it’s such an important part of the history of creativity, this idea of a creative guardian angel. The movie certainly tells you that it’s really in your own head if you believe that it’s true. I just always liked that idea that there was an outside party that could contribute to the success of a creative project. It’s also the idea that Hollywood will embrace anybody and do it quickly. People rise up in this town very fast, and sometimes they’re even criminals, let alone not who they say they are.

Do you think the character you play is a good screenwriter?

I think he’s a good screenwriter going through the exact period that tons of screenwriters are. Ninety-nine percent of writers write for somebody. There’s only a few people in life who ever get to write because they want to and people come to them. Most people write for hire. As those people get older, I think they all get a little scared when the executives become younger than their children; they get a little worried that they’re not going to get those jobs anymore, so they start writing things that maybe they don’t love or they’re not close to. I think that’s sort of what Steven Phillips is….

The distance between the character and you is probably greater than it’s been in any of your other films.

People always like to think everything’s you. I used to answer this question a lot—”Lost in America, is it you?” and I said, “I don’t own a motorhome, I’ve never lost all my money in Las Vegas, I’ve never worked for an ad agency, but sure, why not?” I’m not interesting enough on my own that you’d want to see a film about me. My whole interest comes alive after I create something and can get it on its feet. Why would you want to see me sit in a room all day trying to do that? That’s what Albert Brooks does.

But there is a kind of unspoken contract between you and the audience: you create something imaginary in its circumstances and they’ll believe it’s you up there.

I understand what you’re saying, but let’s go back to somebody like Jack Benny, one of the greatest radio and early television comedians that ever lived. The reason why he was so brilliant was that he did nothing. He would have these long, 40-second takes where he would just stare. But the audience knew him so well that they laughed at those silences. He was known as someone who was cheap, the most frugal, he never paid his employees; this is what people roared at. One of the biggest laughs in the history of radio is: Jack Benny’s walking home late at night and a guy comes out of an alley and says, “Your money or your life.” And Benny doesn’t say anything. And the audience starts laughing and laughing, and finally the guy says, “Your money or your life!” and Benny goes, “I’m thinking it over!”

His whole life, Jack Benny faced this: “Are you really that cheap?” And Jack Benny was one of the most charitable men that ever lived. These older comedians all played their own name. So it got confusing. I’m the last one to look at these characters that I play as being me. I’ve always hated the word neurotic—life is not an easy road for anybody no matter who you are, so all I’m really doing is saying, “Look what happens.”

When I was a kid, 99 percent of the standup comedians just did jokes that had nothing to do with them and you could call them everyman jokes. I don’t know where it happened, but as standup comedy changed over the years, Everyman changed to Individual Man, and that’s when I started. When I played Albert Brooks in Real Life I learned how confusing that gets, because people didn’t know me very well then. I was reading reviews like, “This Albert Brooks should never be allowed to make another film, and he doesn’t know how to handle a family. How dare he be so rough with children.” And I’m going, Holy shit, don’t people get it? So unless you play something so bizarre and unrealistic, you’re always going to get mixed up with your work, which is just the way it is.

I would not have made Modern Romance unless I had that kind of trouble in my life with breaking up. I didn’t do it as much as that character, but I did it enough to be able to write and do that, so for comedic purposes, I take behavior that I might do and I square it. And then you have a performance, you have a movie. You have to be fearless about it, you can’t go, Oh gee, am I gonna come off too this or too that? Don’t make the movie then, don’t do that subject if that’s what you’re afraid of, play a lovable teddy bear. If I think about my next film and think, This could be very embarrassing, I would never do it. You have to commit yourself to the part. If you don’t do that, you have no chance of ever doing it great. I really did feel when Real Life came out that people would automatically go, “Oh, is he brilliant, the way he played that character with his own name.” And I was really surprised when that didn’t happen. I saved the review that said, “Why would Paramount give this idiot the money to do such an important experiment?”

Read the rest of Gavin Smith’s interview with Albert Brooks in the July-August 1999 issue.