By Pablo Suárez in the September-October 2003 Issue

A Road Movie with a Difference

Suddenly announces the arrival of a new Argentine breakthrough

Anything can happen at any time,” says 27-year-old Argentine indie filmmaker Diego Lerman, talking about his debut feature, Suddenly (Tan de repente). “It doesn’t matter if it doesn’t. What’s important is the possibility that it can, and creating a world for it to take place in.” This succinct definition of cinematic verisimilitude perfectly embodies the essence of Lerman’s film, which has won significant critical acclaim, both locally and internationally, over the past year.

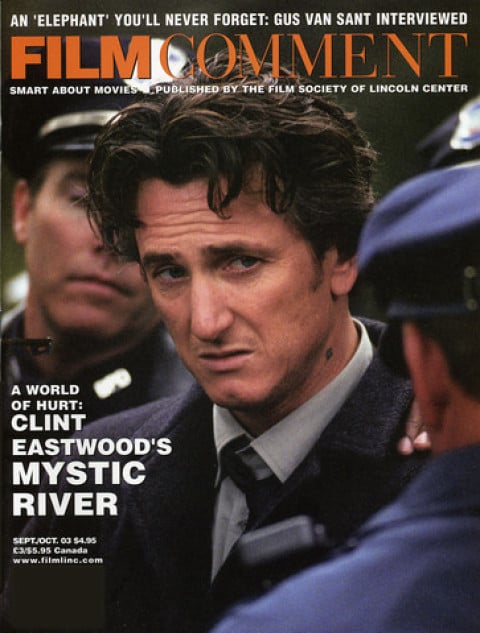

From the September-October 2003 Issue

Also in this issue

This unique sleeper started its slow but steady rise at the 2002 Buenos Aires International Festival of Independent Cinema (BAFCI), where it took both the Special Jury Prize and the Audience Award. It then traveled the festival circuit, making stops in Havana, Locamo, Biarritz, and Vienna, where it won the FIPRESCI Award. The jury there cited it as “a plot-twisting riot-girls road movie announcing the strength of an Argentine New-New-Wave.”

Unlike the vast majority of New Argentine cinema (the work of Martín Rejtman, the movement’s spiritual father, may be the only exception), Suddenly began life as a novel. During the mid-Nineties, Lerman made five shorts, one of which, La Prueba (98), was adapted from local writer Cesar Aira’s book. “It was shot in 8mm, edited on video, and then blown up to 35mm so it could participate in the 2000 BAFICI competition,” Lerman explains. “It won, and the prize was a scholarship at the San Antonio de los Banos Film School in Cuba.” At the time, Lerman was already working on a feature film script, using Aira’s novel “as a mere starting-off point,” whereas the short was more of a conventional adaptation. The feature would eventually become Suddenly, which, like almost all Argentine indie productions, was made on a shoestring budget.

Yet Lerman skillfully managed to turn budget limitations into aesthetic virtues. “I had very little film stock and shot practically no coverage,” he remembers, “so I had to mentally edit a number of scenes prior to shooting them because I knew I wouldn’t have many retakes. There was a great deal of pressure, but at the same time it was good, because it forced me to think seriously about the mise en scene—a lot. Nothing was left to chance. Take the high-contrast black-and-white lighting. In some scenes, it’s ultra-realistic, and I don’t care if it shows. In others, I went for a more classical approach. The idea was to use photography as another tool to reveal what’s beneath the surface of the story, not just for the sake of its beauty. I didn’t have much lighting equipment, anyway, so I couldn’t ask for much,” he laughs.

You can read the complete version of this article in the September / October 2003 print edition of Film Comment.