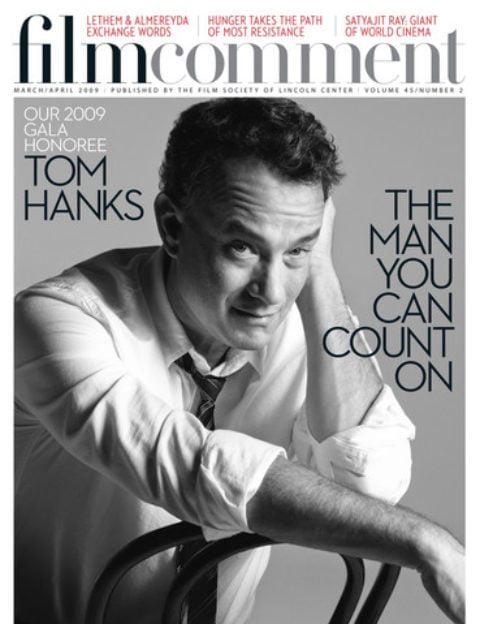

By Beverly Walker in the March-April 2009 Issue

Hanks to You

So Big. That's Tom Hanks, angry young wiseapple. Beverly Walker goes to his comedy store and takes inventory.

Tom Hanks’s confident demeanor is as daunting as Mt. Rushmore and just as effective in discouraging speculation about who those men really are.

From the March-April 2009 Issue

Also in this issue

In his office at Walt Disney Studios in Burbank, California, the 32-year-old actor is courteous and humorous, shrugging off the future as capable of taking care of itself. Charming and intelligent, Hanks carefully maintains a certain distance, as if he had long ago drawn a circle around himself—like a moat.

Come to think of it, most of the characters Hanks has played since Bachelor Party (83) have been detached from the mess they find themselves in. That’s what gets them through, and maybe that’s what got Hanks through a knockabout childhood.

Born in 1956 in Concord, California (north of San Francisco), Hanks was the third of four children. His parents divorced when he was young, and Hanks grew up with his father, who worked in restaurants up and down the coast, settling in the Berkeley area when Tom was a teenager. Stepparents came and went. He married at 20 and has two children, a son of 10 and a daughter, aged 6. Divorced from this first wife, he is currently married to Rita Wilson, his co-star from Volunteers (85).

Hanks undoubtedly made his own life decisions without benefit of parental counsel. His Dennis the Menace appearance notwithstanding, he is well able to look after the store. Hanks’s cheekiness brought him notice in Splash, Nothing in Common, and Dragnet. Yet it wasn’t until Big, his tenth film and riskiest assignment—to skewer the Eighties Male as an overgrown junior-high-schooler—went into release last June that critics saw more than a quirky kid at play. When Punchline followed in September, Hanks’s fully contoured, edgy performance as a tormented stand-up comic more than stood up to critics of the film; it announced the arrival of Tom Hanks as a major player.

Failure to perceive the size of Hanks’s gift reflects more upon the continuing second-class status of comedy in this country than of any startling development or deepening on his part. Comics are still given short shrift when it comes to respect and encomiums. Nonetheless, Hanks is sure to receive an Oscar nomination for one of the two films, and there are those who think he may stun the favorite, Gene Hackman, and win.

Bachelor Party

Most of your characters use humor to keep people at a distance or diffuse hostility, to keep themselves “in a safe place.” Is the comic an isolated figure? Is the comic spirit a figure of human isolation?

I guess the comic is something of a solitary figure. The thing about comedy is you can do it alone. What you get from a comic is his point of view… his philosophy. Even in an ensemble—the Marx Brothers or Monty Python—Groucho is very different from Chico, John Cleese from Graham Chapman, George from Ringo, and so on. You accept their individuality because their playing together does not necessarily make a coherent statement: you’re still reacting to each individual.

Did you hone your comic skills from real life—for example, were you a cutup as a kid?

Not in the sense that I got into trouble, but I never had problems getting up in front of my friends and doing stuff.

It probably is a self-defense mechanism in order to keep the world not just at bay but in proper perspective. The growing up that I did, well, you could easily say, “Oh gosh, what a nightmare that must have been.” But all growing up is nightmarish to some extent, and my siblings and I have always thought that ours was just different from many others, and not necessarily worse. We probably had some advantages over other people.

You had one another.

That’s really it. I grew up with an older sister and brother, and they were the people I was around more than anyone else, including either of my parents. Since I was the youngest of three, less was expected of me. Because I had less at stake, I developed an observational point of view. I was constantly thrown into a bunch of brand-new situations, though I was never intimidated by them.

Your characters have enormous confidence.

That’s probably why I was attracted to them.

Do you recall when you first became interested in movies?

When I was in junior high I remember watching everything from Beauty and the Beast to Seven Samurai on a TV program called Film Odyssey. Later, when I lived in Berkeley, I went to a massive theater called the U.C. It was about to go out of business ’til the guy who owned it decided to show a different double bill every night.

Did any particular movie just hit you out of the blue one day and just set you off on an actor’s path?

[Almost reluctantly]: Yeah, when I was 13 years old, 2001: A Space Odyssey showed me what could be communicated just by image—silent image. By somebody’s vision and camera they could communicate both something as earth-shattering as man’s place in the universe. It was a heady thing. I’ve probably seen the movie 22 times.

It got me into a sensation that you get, whether you’re alone or with two and 20. You sit there completely transfixed… suspension of disbelief and all the other stuff.

Splash

Did you watch the great comedians more than any other actors?

No, I didn’t see my first Marx Brothers movie until I was in college. And I’ve never watched comedies particularly more avidly than anything else.

You began your career in classic repertory under Vincent Dowling, now head of the Abbey Theatre in Dublin. How’d that happen?

It was the biggest break in the world. I was in my third year at California State University in Sacramento. In addition to acting, I was learning to stage manage, work the light board, and so on.

Once, when I didn’t get cast in a show and all my friends did, I went downtown and auditioned for a community theater that was doing The Cherry Orchard. Vincent Dowling was the guest director.

I got cast as Yasha, a servant. In the course of doing the role, I began to work as a stage carpenter on a kind of scholarship basis. Vincent was then with the Great Lakes Shakespeare Festival in Cleveland, and he was attempting something quite audacious—a six-play repertory season. He needed cheap manpower, so he asked a couple of us to come back with him as interns.

During the first season, I got the part of Grumio in Taming of the Shrew. It toured Ohio under a state grant—and that’s how I got my union card. And started making the masterful sum of about $210 a week.

That’s how I began. A lot of flukes but also being able to deliver the goods at the right time. They invited me back the second season to do Proteus in Two Gentlemen of Verona, along with other roles, and I returned the following year as well.

What’d you learn?

To know what is and isn’t important. You have a finite amount of preparation time, and in some cases what’s important is to know your lines and show up on time. It was a pressure cooker.

No discussion of interpretation and acting technique?

You got that from other members of the company. It was an eclectic group with lots of professional credentials—some worked in television, others had studied at RADA or had been with the Guthrie in Minneapolis. And then there was me who was just learning how to walk and talk on stage.

When I finally moved to New York in 1978, I had acting skills but no knowledge of the business. Didn’t even know you had to have a picture and résumé. I couldn’t collect unemployment, so I didn’t have to take a survival job like selling shoes. I auditioned for everything that was going on and connected up with the Riverside Shakespeare Co., a scrappy classical/commedia group that got grants here and there and put on shows.

I met my manager, Simon Maslow, in 1979, and I got a little role in a hack-and-slash movie shot on Staten Island, which got me into SAG. Then I auditioned for ABC, and out of countless people I was cast by Joyce Selznick, a legendary name, in a TV series Bosom Buddies. That was in January of ’80, and by April I’d moved to L.A. It was blind luck.

Volunteers

Let me read some hoity-toity definitions of comedy to you:

Raymond Durgnant: “…a salutary kickback against a too-well-ordered world.”

Aristotle: “…things which are incongruous or exaggerated.”

Schopenhauer: “Recognition of the disparity between reality and ideal concept. The triumph of comedy is that we have recognized the incongruous and can deal with it.”

Bergson: “…an intellectual process because it stems from perceptions.”

How do you approach comedy?

Blindly. I think it takes care of itself.

It’s there in the writing?

Sometimes it’s not there in the writing. It may be there in the theme, but you don’t know if it’ll make an audience laugh or not.

When I say comedy takes care of itself, I mean it’s an assumption the actor has to make—and then pay no attention to. You have to go on to the more specific tasks of actors: to actually walk in this world, to reflect what’s going on in society, to be a breathing character others can recognize.

I consider myself an actor before I consider myself a comedian, but I’m certainly aware that I’m funny and that my movies are comedies. I disagree with the guy who said comedy is an intellectual process. People who intellectualize about it aren’t funny. That’s true about acting in general. But comedy’s more instinctual.

I don’t know if it’s possible to have a specific “approach.” I don’t have a system or even think about it very much. Something happens, but it’s always different. A lot of it’s just common sense.

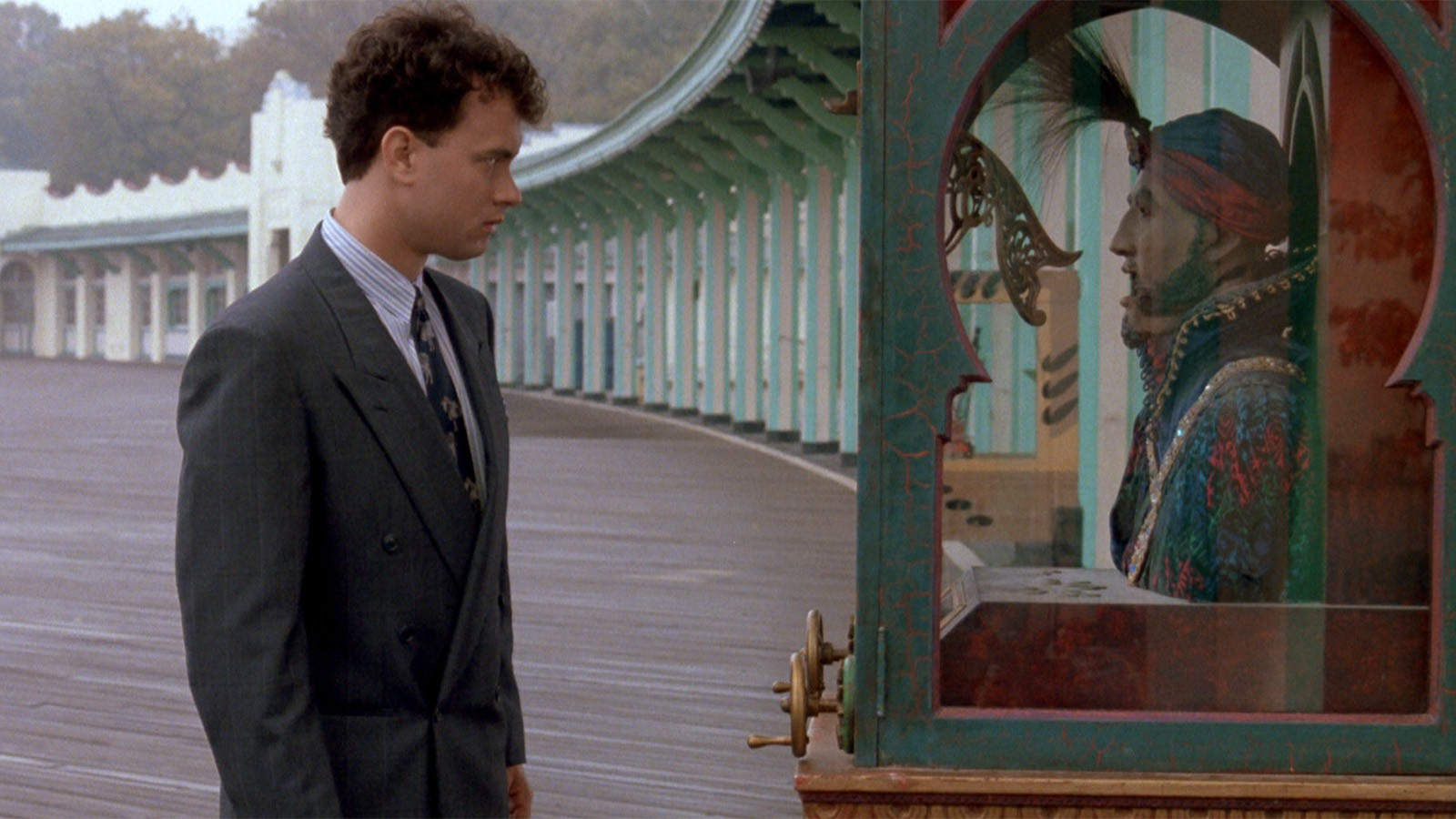

With Big, that certainly was the case. The ground rules were laid out definitively by the script and from discussion with Penny [Marshall]. We called it INSH: innocence and shyness. The two governing traits of this kid.

Did you try out any of that stuff privately before you did it on the set?

Yes, I worked with a videotape at home—just for myself. I did the same thing on Punchline.

You looked at the video to see if what you were feeling inside was being manifested outside?

Yeah.

Do you like to rehearse?

Depends. We rehearsed more on Big than on any film I’ve ever made—for about three weeks before we started—to the point of almost being numb. But it helped in the long run because once you’ve done it so many different ways, you cast off all your bad habits.

On which of your films did you turn a corner?

Nothing in Common [86]. I was involved from the beginning with the producer, Alex Rose, and the guys who wrote it even before Garry Marshall came in to direct. We were all hungry and wanted to prove something, score a touchstone or whatever.

During the eight months of rewrites, after Ray Stark said yes, we talked about what we were going to do with it. I was able to say, “Here’s why I want to do this character, and here’s what I think the movie is about”—from my own selfish actor’s point of view.

It worked despite feeling like two different movies, one about an advertising executive and another about a guy and his parents. Which part did you want to do the most? Or was it both?

Both. I thought that was what was unique about it—life is really hard right next to when it’s really fun… right next to when it’s sad… Life slams against itself.

I also thought it was a timely movie—America 1985. Aging parents, dissatisfaction with one’s career, learning that what lasts is not our jobs and what we do with them.

In short, an awful lot of emotion was invested in the movie, and that was the first time it had ever happened to me. So it really changed me and started me looking at my position in moviemaking in a different way.

Punchline

Was Jackie Gleason a handful?

No, because we all understood that you do it Jackie’s way. It comes with the territory. After all, that’s why you want him in the movie in the first place. Everybody has a different way of approaching comedy, and it’s pretty simple to adjust. Maybe it goes back to working in repertory. You don’t have to like or respect someone in order to work with them.

Did you pick up any tricks of the trade from Jackie?

Not to make excuses for anything. He never assigned blame or showed remorse. He wasn’t theoretical, he just got up and did it, and I had to be ready for whatever came around. There’s a take that actually illustrates that. He caught me in the mouth with his elbow when he opened the refrigerator. Because it was Jackie and a very intense scene, it didn’t throw me. I just kept on going. That’s what you learn about filmmaking, of course—to keep going no matter what. And that’s what Gleason did.

Both Nothing in Common and Punchline focus on young men defining themselves in the world. Why, in Punchline, is the breakdown scene in front of the father never dealt with further?

That’s all there ever was. I don’t think it’s important, as long as you get the sense of intimidation he feels. Otherwise the movie could have become the story of Steven Gold and his father, and that’s not what Punchline is about.

What’s wrong with Steven Gold is that his chromosomes are goofed up. He’s the black sheep of his family, and there’s nothing that’s going to make him feel good about who he is and who his parents are.

I guess you don’t agree that environment makes the man?

It’s a combination of things. But how is it that sociopaths are born in this world? Yes, environment plays a part. Steven Gold’s environment was terrible for him. The hope for his redemption does not lie with his family; he needs to shake off his family… which is the opposite of what Nothing in Common is about.

How often do comics break down like that?

About as much as bank tellers, I think.

What are you doing here at Disney?

I have a relationship with Disney that will last for a number of films that I bring to them or they to me. I don’t know if I have the acumen for this or if I like the process. I did it once before at another studio and the timing was not correct for either of us. But here, these guys are entrenched. They have a philosophy of making movies… it’s like a huge Juggernaut… But it’s no more imposing than somebody else’s style of doing movies.

How do you choose your projects?

It’s an avalanche theory. They all fall down on top of you and eventually you dig your way out with something. I have a manager, an agent, a story editor, and all the people here at Disney, as well as myself reading scripts.

The ’burbs

Your first picture for Disney will be Turner & Hooch. What’s it about?

It’s the story of a man who’s changed by a dog. I’m attracted to it because it contains a filmmaking problem I’ve never faced before—just because a dog is involved. Since I’m connected to him throughout the movie, that means trainers and my own individual work with the dog. It’ll be directed by Henry Winkler. [Winkler was replaced by Roger Spottiswoode in February ’89 after 12 days of shooting.]

Then being at Disney and having this multi-picture pact does not mean you’re going to take the same kind of interest in finding pictures for yourself that many female stars do, for example, Sally Field or Jessica Lange?

My point of view is different. Those ladies are very driven people with a very particular philosophy, which I do not happen to hate. But they also have the acumen tot do it. I couldn’t produce something I’ll be in. Not now. When the time is right, I’ll know it.

How do the people who read for you know what you’ll want?

It’s a gestalt kind of communication that does down among us, in which we understand the big priority that variety is more important than anything else. There is no formula. At the same time, there is a realistic set of guidelines. There’s no reason for me to play a psycho killer who butchers people with razor-sharp hubcaps.

The nature of the movies should be something I haven’t already done. Big was such a character piece… but he was a kid. The ’burbs is an ensemble piece, and Turner & Hooch is about an adult with a responsible job who is changed by the way of something normal and of this world.

There’s an awful lot of kooky guy/straitlaced girl, or vice versa, scripts out there; the Peter Pan syndrome guy who will not grow up, not get involved in a relationship—a ton of that garbage around; or the poor schnook who gets involved in a bunch of shenanigans; and unrequited love: the man who sees a vision far more beautiful than anything he has ever seen before. My objective is to be somewhat surprising, which means I like to be surprised as well as anybody else.

In The ’burbs—weird neighbors move into a dead-end street in the suburbs—it sounds like one kind of movie, but because Joe Dante directed it and Bruce Dern and Carrie Fisher are in it, it ends up taking a different spin.

Someone told me you created such a rich history for your character in The ’burbs that it was incorporated into the film, changing it.

Sometimes there’s more of an opportunity to create than others. Here’s a guy with a great life—a nice house, a wife, a beautiful tree, a nice neighborhood, and he’s happy. Next day, he hates it all. I thought something must’ve happened to him offstage. But what I did is just backstory embellishment that any actor will do. Perhaps from my repertory experience. I don’t ask a director for motivation. If he says, “Go over to the window,” I find the reason myself.

Is a director important to you?

Aspects of a director are. Communication is the key. I consider the visionary aspects of a movie a subjective play on the director’s part. It’s not for me to say to him, “Here’s how I want you to see this movie.” Better I say, “Here’s how I see this guy. If you agree, let’s go, and if you don’t, then please fire me, or walk off the picture or I will, or whatever…”

Is there a particular performer who has influenced you?

Robert Duvall. Though he’s not particularly a chameleon, it took me a long time to recognize him from one movie to another. He’s not unique looking—doesn’t put a hump in his back or do much more than walk a little different. Yet this man keeps entire movies together, as in The Godfather pictures. As Boo Radley in To Kill a Mockingbird, he stood behind a door and communicated something worse than your worst nightmares. He made you feel sorry for him, too. To me, this is a film actor: a man who conveys so much without saying anything.

Dragnet

Do you have any “grand plan” for even the next couple of years?

No plan at all. There are people who try to manipulate their careers all the time, and it simply doesn’t work.

You seem to be in a moment of transition, and in a position most performers would envy. You’re obviously not a beginner anymore; you have a choice of just about anything you want to do; you have power.

The only power I have is the power to say no. Even if I say yes, I still have to convince guys in suits with briefcases and checks that they need to make this movie as well. I have to take advantage of the opportunity when it’s there; I can’t manufacture it. I just have to swing away.

That strikes me as having an awful lot of trust in the world out there to send something your way.

I guess it’s a bit of faith in serendipity.